News

Residential

“Your average gaming computer is like three refrigerators”

August 31, 2015 - “Your average gaming computer is like three refrigerators,” said Berkeley Lab researcher Evan Mills, who co-authored an investigation of the aggregate global energy use of PCs designed specifically for gaming and found that gamers can achieve energy savings of more than 75% by changing some settings and swapping out some components, while also improving reliability and performance.

September 1, 2015 By Anthony Capkun

“It’s remarkable that there’s such a huge overlooked source of energy use right under our noses,” Mills said. “The energy community has been looking at ordinary personal computers and consoles for a long time, but this variant—the gaming computer—is a very different animal.”

Gaming computers represent only 2.5% of the global installed PC base, says Berkeley, but account for 20% of the energy use. Mills calculated that a typical gaming computer uses 1400kWH/annually, or six times more energy than a typical PC and 10 times more than a gaming console.

This corresponds to a potential estimated energy savings of 120TWh globally by 2020, says Berkeley, which is equivalent 40 standard 500MW power plants that would not have to be built.

“When we use a computer to look at our email or tend our Facebook pages, the processor isn’t working hard at all,” notes Mills. “But when you’re gaming, the processor is screaming. Plus, the power draw at that peak load is much higher, and the amount of time spent in that mode is much greater than on a standard PC.”

Mills estimated that gaming computers consumed 75TWh of electricity globally in 2012, or $10 billion, and projects that will double by 2020 given current sales rates and without efficiency improvements.

“There are 1 billion people around the world who are gaming now,” he said. “And it’s a really diverse demographic. There are a lot of women; the median age is 31. And the popularity of these giant desktop gaming computers is growing fast.”

The good news, he says, is that there is ample opportunity—for consumers, manufacturers, policymakers—to save energy. On the regulatory side, displays and power supplies are the only components that have energy ratings today, says Berkeley, and those ratings are voluntary. Additional ratings for motherboards, hard drives, peripherals, and other parts are “an opportunity area”. The gaming software itself can also be designed to use energy more efficiently.

The study measured and charted the performance versus nameplate power consumption of many popular components. One problem the authors found was the variation in nameplate power; for example, graphics processors ranged from 60W to 500W. Their computing performance varied considerably, as well, by as much as five-fold. And there was little correlation between the two, meaning some units that were highest in performance had lower power consumption.

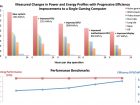

The researchers also built five gaming computers with progressively efficient component configurations, then followed industry protocols for benchmarking performance while measuring energy use. They were able to achieve a 50% reduction in energy use while performance remained essentially unchanged. Additional energy savings were achieved through operational settings to certain components, yielding total savings of more than 75%.

“The huge bottom line here is that gamers don’t have to sacrifice performance to save energy,” Mills said. “In fact, the efficient systems run cooler and quieter, both of which are desirable attributes among gamers.”

Print this page